Your Immune System Has a Body Clock — And Light is Its Wake-Up Call

It turns out your immune cells know what time it is. Literally.

A new study published in Science Immunology has uncovered something remarkable: your first line of immune defense — the neutrophils that gobble up invading bacteria — work more effectively during daylight hours. Why? Because they’re running on circadian time.

Let’s break it down.

Most of us know about the circadian rhythm in the context of sleep. Stay up too late, miss the morning light, or do shift work long enough, and your internal clock starts to drift — a phenomenon researchers call “social jet lag.” But the impact goes far beyond fatigue or grogginess.

Disruption of your circadian rhythm doesn’t just mess with your mood. It affects your immune function too. And this new research helps explain why.

Immune Cells, But Make It Chronobiological

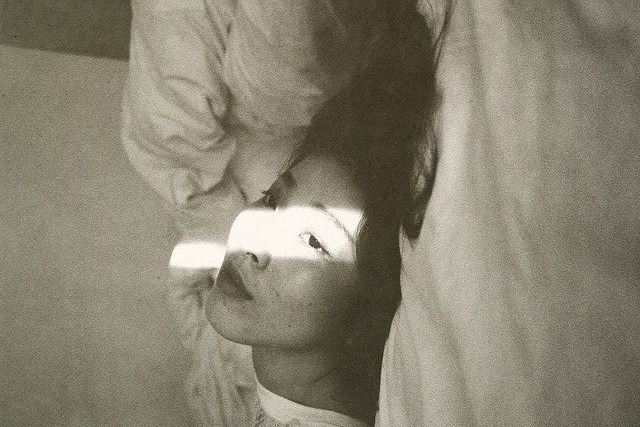

Led by immunologist Chris Hall at the University of Auckland, the study used transparent larval zebrafish — a surprisingly powerful model due to their similarity to human immune systems — to investigate how immune cells behave across the day-night cycle.

Specifically, researchers studied neutrophils. These are the most abundant white blood cells in your body and the first responders to bacterial infection. What they found was striking: neutrophils were significantly better at killing bacteria during the day.

In other words, your immune system doesn’t just “run” — it runs on time.

How Do Cells Know It’s Daytime?

The researchers didn’t stop there. They genetically disabled the circadian “clock” inside these immune cells, and the result was clear: without a functioning internal clock, neutrophils lost their edge. Their bacteria-killing power dropped.

This means your immune cells aren’t just passively responding to threats. They’re tuned into your light-dark cycle — almost like they have an internal alarm clock that says: “Time to go to work.”

And that clock is set by light.

Why It Matters for You

This discovery has massive implications for how we understand inflammation, immune resilience, and even longevity.

If your light exposure is irregular — for example, due to poor sleep hygiene, long hours indoors, or frequent time zone shifts — you may be weakening your immune system without realising it. That nagging fatigue or constant susceptibility to colds could be a sign your immune clock is out of sync.

And if neutrophils rely on daytime signals to operate optimally, then morning light exposure isn’t just a nice wellness ritual — it’s a form of immune training.

What You Can Do

· Get early daylight exposure: Aim for 15–30 minutes of outdoor light exposure in the morning — ideally within the first hour of waking.

· Keep a regular sleep-wake schedule: Even on weekends. Irregular sleep patterns can confuse your circadian rhythm.

· Limit artificial light at night: Especially blue light from screens. This can delay melatonin and disrupt the immune-supportive nighttime repair cycle.

· Track your immunity markers: If you're frequently rundown, consider checking inflammatory biomarkers like CRP, white cell count, or immune-modulating nutrients like vitamin D and zinc.

Where This Is Heading

Researchers are now investigating whether this circadian-driven immune mechanism works similarly in humans — and if it could be harnessed for therapeutic gain. Imagine drugs that activate your immune system when it’s naturally most effective, or treatments that restore immune timing in people with chronic inflammatory diseases.

It's early days, but one thing is clear: light is more than illumination. It’s an immune signal. And understanding your biology’s relationship with time — from your blood glucose to your bacterial defense — may be one of the most powerful levers for lifelong health.

So next time you step outside into the morning sun, know this: you’re not just resetting your sleep cycle. You’re priming your immune cells for the day ahead.

This article was adapted from an original piece by Associate Professor Chris Hall, published in The Conversation on 27 May 2025. It is shared here under a Creative Commons license (CC BY-ND).