Is This Blue Dye Really a Brain Booster?

Is This Blue Dye Really a Brain Booster? Here's What We Know

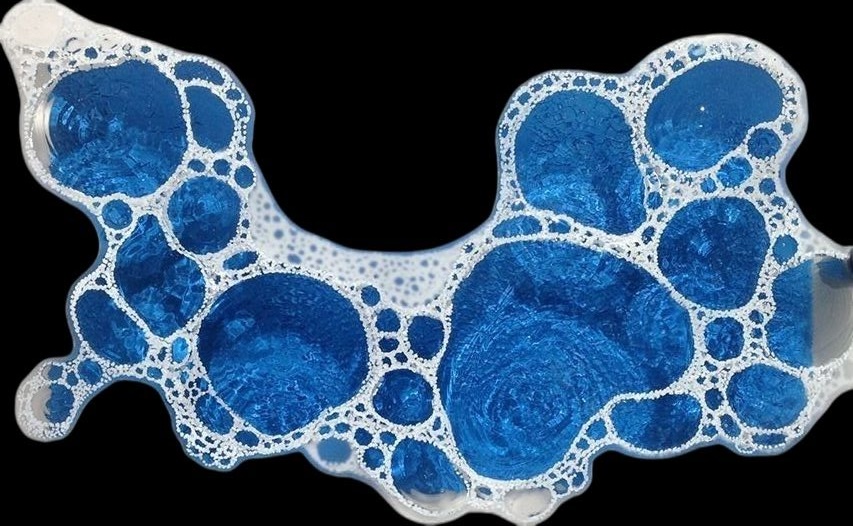

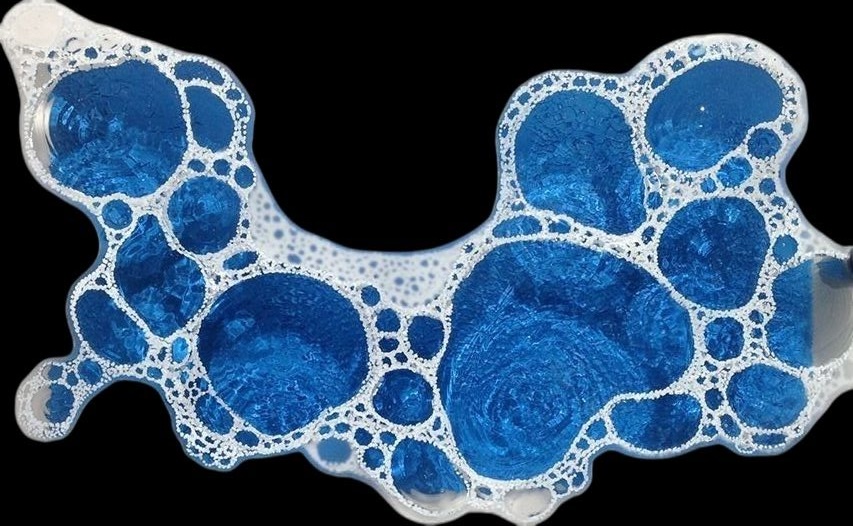

It’s blue. It’s everywhere online. And it’s being talked about as the next big thing for brain health.

We’re talking about methylene blue — a synthetic dye with a long medical history that’s now showing up in wellness circles as a brain-enhancing supplement. Touted for sharpening focus, boosting memory, and clearing brain fog, methylene blue has caught the attention of health influencers and biohackers alike. But does the science actually back it?

Let’s unpack what this compound is, how it works, and what the evidence says — and doesn’t say — about its cognitive claims.

A Dye With Medical Roots

Methylene blue isn’t new. It was first created in 1876 as a textile dye. Its bright, vivid colour made it ideal for staining tissues under the microscope — and by the late 1800s, it was being tested as an anti-malarial drug.

Its superpower lies in its chemistry. Methylene blue can swap electrons with other molecules, like a mini battery. That makes it useful in medicine — especially for treating methemoglobinemia, a rare blood disorder where haemoglobin can’t carry oxygen properly. By restoring haemoglobin’s structure, methylene blue quite literally helps blood do its job.

Doctors also use it during surgery to highlight tissues, and occasionally in cases of carbon monoxide poisoning, septic shock, or specific drug toxicities. In these clinical settings, it’s administered under tight supervision and with precise dosing.

So Why Is It Trending as a Brain Supplement?

Because methylene blue can cross the blood–brain barrier, researchers have become curious about its impact on brain cells — especially mitochondria, the energy producers inside our cells. Some lab and animal studies suggest it might help mitochondria work more efficiently, which in theory could improve cognitive function.

For example:

-

In rodents, it has shown promise in improving memory, learning, and even reducing brain damage after injury or stroke.

-

It’s also been studied in lab-grown cells for its antioxidant and neuroprotective properties.

But here’s the catch: most of this research is early-stage. Human studies are small and inconsistent. One trial involving 26 participants found a slight improvement in memory and increased brain activity on scans — but another found no clear cognitive benefit.

As of now, there’s no solid clinical evidence that methylene blue reliably improves brain function in healthy people.

Is It Safe?

In clinical doses and under medical supervision, methylene blue is generally considered safe. But that doesn’t mean it’s risk-free — especially when self-administered as a supplement.

Here are the concerns:

-

Drug interactions: Methylene blue inhibits monoamine oxidase (MAO), an enzyme involved in breaking down serotonin. When combined with common antidepressants or anti-anxiety medications, it can trigger serotonin syndrome — a dangerous condition marked by agitation, high fever, muscle stiffness, and even seizures.

-

Genetic risks: People with G6PD deficiency — a rare enzyme condition — are at risk of red blood cell breakdown when exposed to methylene blue.

-

High doses: Excessive amounts can raise blood pressure or affect heart rhythm.

-

Pregnancy and breastfeeding: It’s not considered safe in these groups.

The Bottom Line

Methylene blue is not just some trendy wellness fad — it’s a serious compound with real medical uses and fascinating biochemical properties. But that doesn’t mean it’s ready for casual use as a cognitive enhancer.

The science so far is promising but premature. Small human studies have hinted at benefits, but nothing conclusive. And with known risks and complex drug interactions, using it outside of a clinical setting isn’t something to take lightly.

For those curious about optimising brain health, there are better-supported places to start: sleep, blood sugar balance, inflammation control, and nutrient status all have strong ties to long-term cognitive function — and can be tracked and targeted through the right biomarkers.

Methylene blue may have a future in neurological medicine. But for now, it’s not the silver bullet it’s being marketed as.

Lorne J. Hofseth is a Professor and Associate Dean for Research at the University of South Carolina, where he studies inflammation and cancer. This article originally appeared in The Conversation and is republished under a Creative Commons license.